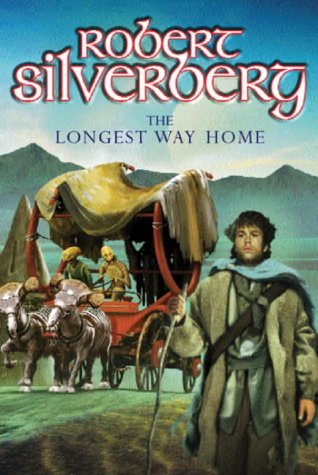

The Longest Way Home:

The Peasants Are Revolting

by Jon Davis

The parallel of the social situation on Homeworld with the American South in

the time of slavery is obvious: the Masters use much of the same rhetoric as

slaveholders did ("It's for their own good." "They are like

children, unable to govern themselves." "They are naturally unsuited

for leadership."); after centuries of dominance, some Masters are surprised

to learn their servants are not content; men of the Master class frequently take

slave women as sexual partners, but would not consider them as wives; and so on.

There are, of course, differences. Homeworld has no nations where slavery is

outlawed; there seem to be no factions of Masters opposed to the status quo;

although there are general physical qualities that differentiate Masters from

Folk, they are not what we would call "racial" and indeed there seems

to be a variety in skin tone among the Masters.

The parallel of the social situation on Homeworld with the American South in

the time of slavery is obvious: the Masters use much of the same rhetoric as

slaveholders did ("It's for their own good." "They are like

children, unable to govern themselves." "They are naturally unsuited

for leadership."); after centuries of dominance, some Masters are surprised

to learn their servants are not content; men of the Master class frequently take

slave women as sexual partners, but would not consider them as wives; and so on.

There are, of course, differences. Homeworld has no nations where slavery is

outlawed; there seem to be no factions of Masters opposed to the status quo;

although there are general physical qualities that differentiate Masters from

Folk, they are not what we would call "racial" and indeed there seems

to be a variety in skin tone among the Masters.

I was struck a number of times by the similarity between Silverberg's Homeworld and the general situation Ursula Le Guin has written about in her recent stories.

In an odd coincidence of timing, I first read the premise of The Longest Way Home just after getting a copy of The Pueblo Revolt. I was immediately struck by the similarity of the situations: a seemingly docile underclass rises up against a seemingly more powerful ruling class, taking them by surprise.

As much as I enjoyed reading The Longest Way Home, one thing was foremost in my mind, and it was never resolved. Would Joseph be the Master who would topple the system? The novel ends with Joseph's return to House Keilloran, before this final conflict really begins. And while there have been some big changes in Joseph's attitude, we have only seen him ask himself questions: "What kind of Master will I be?" He has not made any sort of decision or resolution on the matter. I don't quibble with Silverberg's choice to not tell us how the Liberation ends up. He is telling Joseph's story, deliberately small and personal, not a political epic which would require much more length. For a while I was bothered by the fact that when the book ends, we have not seen Joseph made any sort of decision regarding how he will live his life after his journey, now that he has seen what he has seen and knows what he knows. To virtually any reader today, it is a given that slavery is wrong and that all people should have equal rights and opportunities, but to Joseph, raised inside the system and not questioning it, it would not be so obvious. For Silverberg to have Joseph stare into the sunset and take a solemn vow to make things right for the Folk, much as it would provide moral satisfaction to readers, would not be true to the world he created. Maybe Joseph will someday help the Folk gain their freedom, but such a profound change would be poorly served by such a melodramatic scene. Leave that to Hollywood.