Robert Silverberg was born in New York City on 15 January 1935 to Michael and Helen Silverberg, an only child. He tends to keep his personal life to himself, but he has made allusions to being a lonely and bitter child who found a sort of release in science fiction and fantasy.

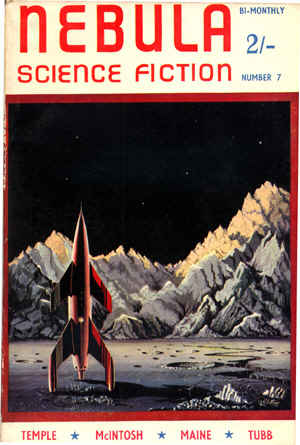

In 1949 he started a science fiction fanzine called Spaceship and

made his first professional sale to Science

Fiction Adventures, a non-fiction piece called Fanmag,

in

the December 1953 issue. His first professional fiction publication was

Gorgon Planet

in the February 1954

issue of the British magazine Nebula

Science Fiction. His first novel,

Revolt on Alpha C, was published

in 1955.

In 1956 he graduated from Columbia University, having majored in

Comparative Literature, and married Barbara Brown, an electronics

engineer specializing in radar and optics

(according to a dust-jacket

bio). His literary background would surface eventually in his writing, but

for a time, he seems to have kept the straight

separate from the

science fiction he wrote, as it was pure adventure stuff with little that

would indicate interests beyond the typical science fiction of the day.

After those initial sales, he started publishing short stories in the pulp

SF magazines, turning them out at a tremendous rate and earning a

Hugo award for his promise (the youngest person

ever to do so). In the summer of 1955, while still pursuing his education,

Silverberg had moved into an apartment in New York that would profoundly

change his life. Randall Garrett, an established science fiction writer,

lived next door; Harlan Ellison, another promising young novice, also lived

in the building. Garrett introduced Silverberg to many of the prominent

editors of the day, and the two collaborated on many projects, often using

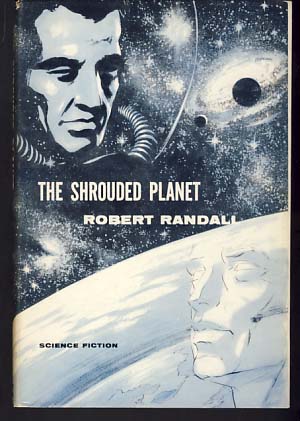

the name Robert Randall. Three of the stories they wrote together,

The Chosen People

,

The Promised Land

, and

False Prophet

, became the 1957 novel

The Shrouded Planet. Other

stories and novels followed.

In addition to the collaborations,Silverberg was writing so much on his own, and selling so much of it, that he was obliged to publish under a number of pseudonyms to avoid oversaturating the market. Thus were born David Osborne, Ivar Jorgenson, and Calvin M. Knox, among others (see pseudonym page). He had the ability to write on demand for his editors, so if asked, he could produce a story with a given theme and a given length in a day or so. He seems to have been motivated in part by a fear of what he saw other writers reduced to: possessing talent but unable to support themselves decently with writing. Between 1957 and 1959, he published (using various names) more than 220 short works and eleven novels, most of which have never been reprinted. He also wrote a large number of other genre stories, including mysteries, westerns, and erotica. As a writer myself, I find this mind-boggling. No wonder he eventually burned out.

During this time, he has admitted that he became his own worst enemy, so addicted to the sale that he didn't utilize his own best abilities. Writing became a job to him. He produced what he thought the market wanted, produced it quickly and well enough to sell, but no better. It seems as if he lived as the extension of the lonely boy with the escapist fantasies, not knowing how to integrate the literate adult into his professional life.

In 1959, Robert Silverberg announced that he was retiring from science

fiction. In spite of this retirement, books and stories continued to appear,

mostly anthologies of collected stories written during the earlier days and

expansions of previous short works into novels. His writing in the early

sixties was mostly outside the field of science fiction. He wrote many

nonfiction books, starting with Treasures

Beneath the Sea in 1960. Then, with

Lost Cities and Vanished Civilizations

in 1962, Silverberg moved into the lucrative

(as he called it) area

of hardcover non-fiction for younger readers. Between 1960 and 1972, he

published approximately 70 nonfiction books, mostly in his preferred fields of

pre-history, archaeology, and exploration. Also during this time he wrote

a large number of soft-core pornography novels under the name Don Elliot or

Eliot.

Frederik Pohl, then editor of Galaxy, is credited with drawing Silverberg back into science fiction by convincing him that a new, more literate kind of story would sell. Silverberg's new stories showed a much greater depth of characterization and emotion than his earlier work. The plots deepened, the characters started to come to life. He started taking his examples not just from the most successful SF writers of the day, but from the best writers in all fields, from classical Greeks to modern masters, finally integrating that other side of his personality into his work. Things got less predictable.

By the end of the sixties, Silverberg almost exclusively indulged the darker side of his personality, telling stories of loneliness and isolation. Freed from the practical necessity of a heroic, happy ending (due to changes in taste in editors and readers), Silverberg's stories took on a darker tone, often ending on a down note or with ambiguity. Along with these heavier themes came a quest for transcendence which surfaced in many stories in many ways. If human life is filled with inevitable misery, there must be an alternative somewhere.

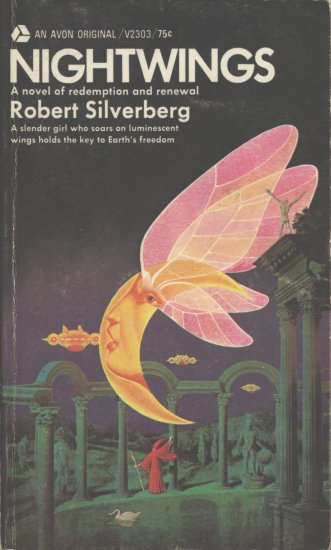

The major works of this period are

Nightwings,

Dying Inside,

Tower of Glass,

Thorns,

Downward to the Earth,

The Book of Skulls,and

Shadrach in the Furnace. Among

the excellent shorter works are

Sundance

,

Born with the Dead

,

Caliban

,and

In Entropy's Jaws

. Virtually everything

dated from about 1969 to 1974 is of high quality. It is this period which

produced the main concentration of awards.

By 1973, he was once again starting to suffer from what we would now call burn-out, though of a different sort than in 1959. That other time, he was frustrated by the low standards prevalent in the field; now he was feeling drained by the intensity of effort required to produce the kind of writing he demanded of himself. He stopped writing short stories altogether, and then turned out a few more novels before publicly announcing his retirement (again). His prodigious output during the preceding decades made this departure both necessary and possible.

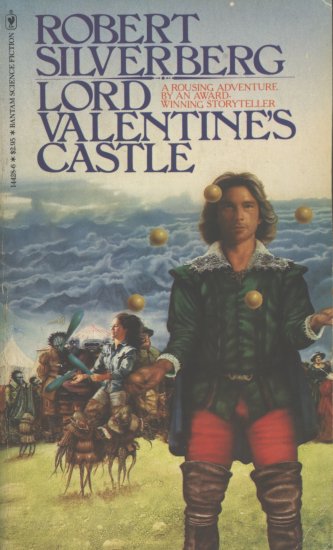

Despite much pleading from editors and fans, he held out until 1978,

when he found himself working on what became

Lord Valentine's Castle. The

retirement revealed itself as only a sabbatical. It wasn't

until 1980 that he returned to the shorter forms, with

Waiting for the Earthquake

, which he

had promised Harlan Ellison (in 1975) for the

http://majipoor.com/publications/display/806">Medea collection.

In general, the works of the 1980s and 90s have been longer and much

more satisfying, with great depth of character and plot, though perhaps

lacking the personal intensity of his early 70s work. One of the things

that always strikes me about Silverberg's later works is the loving

touch he uses with all his characters, even the bad guys.

His writing

is non-judgmental to the characters, presenting them as people

with their own thoughts, lives, and motivations, no matter how different

from our own they may be. Even the cannibals are given fair treatment.

This is not to say the stories are dull or lack in action. Far from it.

There is plenty of conflict. You just get to see more than one side of

the issues. Who needs cardboard, cliché-spouting villains, anyway?

On a personal level, the 1980s brought some more changes: he divorced his first wife Barbara in 1986 and married writer Karen Haber the following year. He has collaborated with Ms Haber on a number of projects, notably the novel The Mutant Season. They have also edited several anthologies together.

Some of my favorite novels of the post-Valentine era are

Star of Gypsies,

Tom O'Bedlam, and the

Majipoor books (especially the initial three:

Lord Valentine's Castle,

Majipoor Chronicles, and

Valentine Pontifex). I've also

greatly enjoyed two books which are not science fiction:

Gilgamesh the King and

Lord of Darkness. Excellent

short works abound in these recent years; among the standouts are

Enter a Soldier. Later: Enter Another

,

House of Bones

,

Our Lady of the Sauropods

,

The Pope of the Chimps

,

The Secret Sharer

,

Thebes of the Hundred Gates

, and

A Thousand Paces Along the Via Dolorosa

.

He now lives in the San Francisco area with his wife, Karen Haber. His most recent publications include the novels The Alien Years and The Longest Way Home, plus the final Majipoor books, a trilogy set long before the time of Valentine (Sorcerers of Majipoor, Lord Prestimion, and King of Dreams). In addition, he has edited three big collections: Legends and Legends II (fantasy) and Far Horizons (SF). Many of the best works of the 70s are now in print again, and 2003 brought the publication of Roma Eterna. In 2004, the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America presented him with the Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master Award.

He's come a long way from the cocky kid from New York cranking out the wordage as fast as the magazines would buy it.