Man of Many Bodies

by Robert Silverberg

writing as Ralph Burke

Here is a story from 1956, reproduced in its entirety. While there have been

many collections of Silverberg's work from the 1950s, somehow this one has escaped

the light of day. Of it, he says, I looked at

Man of Many Bodies

this

morning and damned if I could remember having written it. But undoubtedly it's

my work, because I mention several of my favorite composers, painters, and writers,

some of them so esoteric that it's got to be my story.

Since Harry Glenn was

only about five-feet-seven or so, and not very hefty,

it didn't seem fair to him that he should have to move over. The burly drunk in

the black turtle-neck sweater wasn't being ethical about the whole thing.

Harry told him so.

Since Harry Glenn was

only about five-feet-seven or so, and not very hefty,

it didn't seem fair to him that he should have to move over. The burly drunk in

the black turtle-neck sweater wasn't being ethical about the whole thing.

Harry told him so.

You're not being ethical about the whole thing,

Harry said.

The drunk turned slowly to face him. Look, buddy, I told you to shove

over and give me more room at the bar. Either you do it or I'm going to pitch

you out of the door. Got me?

I refuse to let you push me around,

Harry said firmly. There was an

ethical matter at stake here; he was a small man, and, if anything, it was the

other fellow who was taking up too much room.

Listen, pipsqueak, I mean what I say.

In one smooth motion the big

man scooped Harry up, propelled him through the door and out into the street,

where, with a majestic flip, he sent him spinning down into the gutter.

Pick on someone you own size next time,

the drunk shouted derisively,

and then he went back inside.

Harry remained sprawled out on the street, dangling half over the curb, more humiliated than injured. A couple of people went past as he lay there; he heard their sympathetic clucking, but there was, of course, no attempt to help him to his feet. Not in New York.

Harry drummed his fingers against the tarnished metal rim that ran along the curb. He figured it was wiser just to lie there, letting his anger slowly melt away into a sort of cosmic disgust at the situtation whereby such a bold, proud spirit as his should be allowed to be put into a body so inconsequential, so completely inadequate to contain it, than to go back inside the bar and get clobbered twice as hard.

Finally the rage subsided, and he began to grow more philosophical about the whole thing. There would always be big guys to push the little ones around, and good-looking guys to snap up the girls the homely fellows never got, and there wasn't much that could be done about it.

That's what you think,

said a small, child-like voice which

seemed to emanate from a point about three inches from Harry's left ear.

Harry rolled an eyeball quizzically to the left and saw a tiny figure, no more than an inch or two high, sitting in the gutter astride a curved piece of metal that appeared to be one of a pair of handcuffs. Harry shut his eyes. When he opened them, the figure was still there.

I'm not drunk,

Harry told himself firmly. I wasn't in there long

enough to get drunk. I am not drunk!

Of course you aren't,

the tiny being agreed. Its voice was impossibly

high. But you're tired of being pushed around. And that's why I'm here.

Harry started to lift himself to his feet, convinced he must have hit his head

in the fall, but as he began to stir the little man said, No, don't get up.

It's easier to talk when you're down here on my level.

Fair enough,

Harry said. I'll stay here. It may be safer, anyway,

in my condition. Aren't you supposed to be pink, with a long trunk and a tail?

Not at all,

the other said. Don't be facetious. My name is Quork,

and you can believe in me or not. I'm a demon by trade.

At that, Harry emitted one snort that nearly blew the little man away.

Hey! Cut that out!

Sorry,

Harry said. But you—a demon?

I'm a small one,

the demon said, a little crestfallen. But it's

not your place to poke fun at me—you runt.

That's very true indeed,

Harry said, reflectively. I apologize.

One small person shouldn't laugh at another. What's your specialty?

You,

the demon said. I'm in charge of small, pushed-around

individuals like you—or myself, for that matter. My employers have

decided it's time to give you a break.

He indicated the single handcuff

lying in the gutter. Here. This is for you. Put it on.

He climbed down from the handcuff, and Harry reached out and took it.

What does it do?

he asked.

It provides complete personality projection,

the demon said,

rolling the big words glibly off his forked tongue. When you're wearing

it, you can take any human shape you want—within limits, of course.

Harry put the handcuff around his wrist and snapped it shut. It clicked resoundingly.

There,

Harry said. If I'm going to have hallucinations, by God,

I'm going to play right along with them. What do I do now?

Just—use it,

said Quork.

Wait a minute!

Harry said, but the small demon had vanished,

leaving him alone in the dark, moonless city street. Harry shook his head

thoughtfully. He must have suffered a concussion when that drunk hurled

him down. Demons, yet! He started once again to clamber to his feet,

and was startled to find sudden help in the form of a strong hand inserted

roughly under his arm.

Lemme give you a hand,

growled a heavy voice. Harry got to his

feet, rocking unsteadily a little, and looked at his Samaritan.

Hello, officer,

he said mildly. Nice evening, isn't it?

Ah—I was just taking a walk when...

Swell one for staying sober,

the policeman said. Suppose you

come along with me, friend. The mayor's latest keep-the-streets-clean

order includes you.

Now just one minute,

Harry protested. He was indignant. I'm

just as sober as you are. I was in a brawl just now, through no fault

of my own, and I was just getting up from where some bully threw me.

You can't take me to jail for that!

Look here, pal, you can tell—

I know,

said Harry. But I don't want to talk to

the judge! I want to go home, and clean off this mud, and work on my

new poem. I won't spend a night in jail, officer! I'm as sober as you

are!

he repeated.

That's a laugh,

the policeman said, and immediately broke into

uproarious laughter which echoed up and down the quiet streets. Me,

a drinking man! Why, I haven't touched the stuff in twenty-eight years,

ever since I joined the Force, and I'll swear by my sainted grandmother

that—

But Harry had an idea. He glanced at the gleaming handcuff that still

encumbered his wrist, and said, All right, Sergeant. I'll test your

sobriety, and if you're sober I'll let you take me away. Suppose

you tell me what I look like,

Test my sobriety? You worthless rummy, playing games with me? Okay,

I'll play.

He stepped back and looked at Harry. Faith, man, you're

a puny little chap in a tweed coat, with not much hair on your head and

not a muscle in your body! Does that tell you how sober I am?

Come along, now!

Harry rubbed the handcuff gently with his left thumb, hoping that was the right thing to do. He visualized a stevedore, six-feet-four or so, with arms like rhinoceros legs and an ugly red scar running diagonally across his face. Complete personality projection, he thought.

It had an instant effect. The policeman's eyes widened in horror;

he jumped back and exclaimed, Now where'd you come from

just now? And what happened to the little guy? What kind of funny

business is this?

I'm right here, officer,

said Harry, reverting to his natural

form. The officer blinked, stared around the street, and reverently

took off his cap, revealing a totally bald head.

Now where'd that big ape go?

he asked, puzzled.

I've been here all the time, Mack,

Harry said, turning

into the stevedore once again and lowering his voice by at least an

octave.

That was all the policeman was going to take. He slapped his cap

back on, muttering, Twenty-eight years, never touched a drop,

and turning, he dashed away.

Harry watched him go tearing down the street and around the corner, and listened to the clatter of his heels in the distance, until finally all was silent again. Then it was his turn to react. He sat down limply on the edge of the sidewalk.

Dream? Who knew? Hallucination? Probably.

Complete personality projection. The stevedore was one of many men who lurked within the negligible body of Harry Glenn, bottled up inside him. Now, he could be freed.

Harry smiled. He had a few old scores to settle while this strange power lasted.

He turned and entered the bar, pushing the door aside with unfamiliar gusto, and walking to the counter with a totally new vigor in his stride.

The drunk who had pitched him out half an hour before was still sitting there, hunched up on his stool, cradling a double Scotch in his giant paw. Harry took a deep breath and walked over to where he sat. He tapped the other on the shoulder.

Pardon me,

he said, purposely making his voice even meeker

than usual, would you mind moving over just a bit?

You back again?

the drunk roared without looking up. This

time I'm gonna pulverize you!

He put down his drink and whirled

sharply. The ugly visage of the stevedore-projection greeted him.

I'll—ulp! Where'd you come from?

There was

new respect in the drunk's voice. I mean—I thought you

were someone else.

I am,

Harry said mysteriously. Step outside a minute,

Mack.

Hey! Hold on! I didn't do nothin' to you!

Don't matter,

Harry barked. Let's get outside.

To

make things even better, he reached out and casually flicked the

other man's drink to the floor.

The reaction was immediate. The drunk uncoiled from his chair, primed to fight anyone or anybody. Harry dragged him outside.

They squared off, while a little crowd of bystanders from the bar came out to see what was going on. For one terrified moment Harry wondered whether his personality projection was only an illusion or really a real thing, and then the drunk threw a wild swing at him and there was no time for conjecture.

Feeling a thrill of battle he had never known before, Harry pushed aside the blow easily and stepped inside the other's guard. His projected body moved marvelously; two quick punches and it was over. A right, a crossing left, and the drunk went sprawling down into the gutter, landing about where Harry had been not long before.

Next time move over,

Harry said. He rubbed his knuckles

and went back inside the bar.

A double Scotch,

he said loudly.

He got home just as the sun was coming up. He was more than a little overhung, but it had been worth it, just to see the expression on the drunk's face as he had gone crashing into the gutter. So that was what it was like to be able to bully people? It was a good feeling, Harry thought, though he knew there wouldn't be much pleasure to be gained by it any more. Once was enough; one bully paid back, and he was satisfied. He was not, after all, a vindictive man.

A shave and a shower refreshed him; he rummaged around in his refrigerator and managed to put together a meager breakfast, and then, closing all the doors that sealed his miniature kitchen off from his living-room-cum-bedroom-cum-office, he sat down in his one big armchair to plan his day's procedure.

Assets: one new, apparently unlimited power.

Liabilities: the disadvantage of not knowing how long the power would last, where it had come from (it couldn't really have been given to him by a two-inch-high demon!), or how reliably it would function.

He decided to make the greatest use of his new ability, for the greatest good of Harry Glenn, as quickly as possible. He drew up a list of situations in which being able to take another form could be of some use to him.

Inside of fifteen minutes, he had a hundred different items on his list, most of which he immediately rejected as being completely unethical. He was determined to make use of the power only in an ethical fashion.

Still, there were plenty of things left that could be juggled into his code of ethics, with a little shoehorning by way of an assist. For instance, there was that literary magazine—

Two months before, he had timidly taken a sheaf of his best

poems down to the editorial offices of Ipso Facto,

one of the most respected of the little literary quarterlies.

In a sequence of events that proved entirely humiliating, he was

first refused admittance, then finally admitted and sent to the

advertising director, who listened to about three words of his

stammered explanation and shunted him down the hall to the

personnel manager, where he was told, bluntly but politely,

Sorry, we're not hiring any office boys this week,

and

he was bustled out of the office before he had a chance to show

any of his poems to anyone.

That, he decided, was all going to be fixed. He leafed through his portfolio, winnowed out about five of his best pieces, and slid them into a manila envelope.

On his way downtown, he toyed nervously with the poems, reading them over and over again, trying to comvince himself that someone might find them worth publishing. He had never been anxious to submit anything, always unsure of himself. But now—now was his moment!

At last the subway arrived at Sheridan Square, and he got out and followed a twisting street to the address of the offices of Ipso Facto. As he got in the elevator of the imposing building, he furtively rubbed the handcuff and felt a change come over him.

He stepped out on the sixth floor and majestically threw open the door, throwing back his mane of red hair as he entered. He strode over to the receptionist and asserted himself.

I'd like to see the Poetry Editor,

he said firmly.

My name is Glenn.

He waited expectantly.

The girl at the desk looked up. Her eyes widened. Why,

of course, yes, Mr. Glenn,

she said. How wonderful you

have come to see him! His office is right down there!

Thank you,

Harry said, and followed the direction

her forefinger indicated. He heard the excited whispers as he

moved in a stately fashion down the hall.

He knocked on the Poetry Editor's door.

Come in,

said the editor's voice, and Harry entered.

What the editor saw was a young man, six-feet-three in height,

with a classic profile, tapering, sensitive fingertips, and

flaming red hair sweeping back in an impressive pompadour:

Harry Glenn's idealized picture of the Harry Glenn he should

have been.

Hello,

the editor said, looking up from a desk buried

with manuscripts. He was a thin, tweedy-looking man with

hornrims and an owlish appearance.

Mr. Crawford?

Crawford nodded. My name is Harry Glenn,

his voice was

a throbbing, commanding baritone. You may have read some of

my work elsewhere.

It wasn't true, of course; Harry was yet to see print for the

first time. Crawford frowned, obviously trying to recall where

he had seen some of Harry's poetry, and then, deciding

it was best to agree, smiled and said, Yes, of course. Some

very impressive work, as I recall.

Thank you,

Harry said casually. He flipped the envelope

down on the editor's desk. I've brought you some of my new

work to consider. Tossed them off last night, but I thought your

mag might like them.

Harry stared compellingly at Crawford for a moment.

Well, thank you very much, Mr.—Mr. Glenn,

the

editor said. He gestured at the heap of manuscripts. I'll

give your work a preferential reading, you may be sure.

You'll hear from me in a week to ten days.

Harry—the real Harry, down inside the red-haired

personality projection—fought down a wild desire to bow

down in gratitude and crawl out of the office backward, and

said instead, Well, that's too bad. I've got to make a stop

to see some of my friends over at Quondam Quarterly,

and I might just as well take these as long as you can't manage

to look at them sooner.

He reached for the envelope, but Crawford was quicker. He

snatched up the poems. Maybe you'd better let me look at

them first, Mr. Glenn. Our rates are so much higher

than Quondam's, you know, and I needn't mention

the prestige—

Well, all right,

Harry said, pretending reluctance as

well as he could. Glance through them, then.

Certainly, sir.

Crawford seemed utterly cowed by

the flaming-haired, towering poet. The editor took Harry's

poems from their envelope, licked his lips contemplatively,

and settled down to read.

Ten minutes later, Crawford was typing out a voucher for the purchase of five poems, to be run in a special portfolio in the forthcoming issue of Ipso Facto.

Very fine work indeed,

the editor said.

It's all in the approach, Harry told himself, as he shook hands with Crawford, boomed his farewell, and headed briskly out of the office. Editors, he thought, have to be frightened into buying things by newcomers; a perfectly good poem from meek little Harry Glenn would never even get read, but this new Harry Glenn—

He patted the handcuff affectionately as he made his way through the crowded office to the elevator. This was the start; from now on, he was going in just one direction—up.

He pressed the buzzer. As he did so, he was startled by a deep, throaty feminine voice coming from directly behind him.

Well,

she asked. Did you sell?

Harry turned to confront one of the most delicious-looking girls he had ever seen. She was tall—about five-eight or so, Harry estimated—with golden-blonde hair pulled back tight from her forehead and tied into a two-foot-long ponytail in the back. She was wearing a tight, wrist-length sweater and an even tighter skirt, and the eye-stopping figure thus revealed was worth three of four second glances, and then some.

Sell?

Harry asked, too preoccupied with her shape to

be able to focus his attention on what she had asked. Oh—yes,

of course. They took five poems of mine; they're running them

as a portfolio next issue.

How grand!

she said, flashing brilliant white teeth.

I've just placed my novel with them, you know. They're

splitting it into three novellas, but I really don't mind.

Come,

she said, as the elevator arrived. I think we both

ought to celebrate our respective successes!

Harry started to say something, but his personality projection

carried him along on her impetus, and he merely smiled gaily and

said, Wonderful! How about lunch at the Flying

Dutchman?

Of course,

she said, radiating warmth and desirability.

What better place for two newly-successful literary artists!

And then we can have cocktails at my place, of course.

Of course,

Harry agreed. Behind his back, he squeezed

the handcuff joyously, and muttered a silent blessing for Quork,

that miniscule demon.

Her name was Brenda, she was a writer and an artist, and she lived in a cold-water flat on MacDougal Street. She had been working on her novel for a year; it embodied her whole life's experience in a new artistic synthesis, and to hear her talk it was quite a story.

As the afternoon wore on, and cocktail succeeded cocktail until the martinis became dry to the point of dessication, Harry found himself falling wildly for this radiant goddess of a girl. This, he thought, was the sort of girl he deserved to have, and the sort of girl he would never have dared approach in his old body.

They discussed everything from Bach to Bartok, Titian to Tanguy, Jonson to James Joyce. They were a perfect pair; every interest, every taste seemed to match. By five in the afternoon it was all settled: they would leave the next day for Taos, New Mexico, and live on a quiet hill, raising goats and pouring forth a stream of novels and poems that would astound the literary world.

There's just one catch,

Brenda said, pouring Harry a

martini straight from the gin bottle (there was no more Vermouth).

I don't have a cent, and Ipso Facto won't pay us

for three months. Unless you're loaded, I don't know how we're

going to get out there.

Hmmm,

Harry grunted. Is a problem.

He downed his

martini. But don't worry about it. I'll have the cash by

tomorrow, and we'll take the first plane out there,

he said

grandiloquently.

Done!

she cried. Suppose you beat it uptown now,

and start packing. I'll do the same.

A little later,

he said. We're not in that

much of a hurry.

He took her hungrily in his arms, and pulled

her close to him.

When the euphoria wore off, about five hours later, Harry found himself back in his own uptown room, alone, still glowing a little around the edges.

Brenda. It was almost unbelievable. But there were problems.

First, he had no money, and no prospect of getting any.

Second—and this was the big one—what happened if the power left him, suddenly? What if Brenda were to awaken some morning, in their New Mexico paradise, and find by her side, instead of the god-like man she knew, a small, utterly unimpressive little fellow not quite her own height? Harry shuddered at the thought.

He thought of Quork, the small demon. Could Quork have been so sadistic as to give him a power that would fail him just when he needed it most? It didn't seem likely; at least he didn't want it to seem likely.

I'll risk it,

he said out loud. The handcuff seemed to

be glowing on his hand, and he felt a new surge of confidence.

He'd remain six-feet-three forever, of that he was sure. The

power would never fail him. It would mean maintaining an

uneasy pretense for the rest of his life—but it was worth

it for Brenda.

That left the problem of money. That was easy; all of his old ethics were swept away past him, in the face of his new life with Brenda.

He'd rob a bank. He had a foolproof disguise.

At nine the next morning, he entered the largest and busiest bank in the neighborhood, feeling calm and self-possessed, and wearing the outward image of a bald, middle-aged man. He spent some fifteen minutes wandering around the bank floor, studying the way the bank was situated. Then he drew a convincing-looking toy gun from his pocket, summoned all his powers, and stepped to one of the teller's cages.

Ten minutes later, he calmly walked away, unnoticed, with three thousand dollars in small bills in a thick envelope in his pocket, and, as the alarm sounded, broke into a dash and started to run. He got outside, turned into a freckle-faced teenager, and vanished into the crowd before anyone saw him.

On his way down to Brenda's in the subway later, sitting in an empty local surrounded by two suitcases that held all the personal possessions he intended to keep, he chuckled to himself over the account of the robbery in the afternoon paper.

The holdup was one of the most daring ever committed,

the story said. And not the simplest part of the whole

operation was the conflicting set of reports turned in by

the witnesses. The teller who handed over the money swears

that the bandit was five-feet-eight and bald, while a man

standing nearby reports that he was about six-feet-two,

with a crewcut.

That had been the hardest part, Harry thought—projecting different things to different people. But it had worked; it had worked magnificently. He'd fooled them all, left them totally confused.

Other descriptions of the bandit were similarly at variance

with each other,

the account went on. He was dressed

either in a plain brown suit with brown necktie, or sports

clothes without a tie; his weight was either 160 or 210

pounds.

Police Commissioner Reilly, commenting on the bizarre

aspects of the case, says his men are working on the solution

of the robbery now, and at present the teller has been held for

further questioning.

Harry nodded. It was too bad the teller had to get involved in the thing, and too bad to take innocent folks' money. But, Lord knew, he'd been scrupulously honest all his life, and now that his one big chance had come it wasn't too serious to commit one little bank robbery, was it? After all, he needed the money so badly.

He finally reached his destination and got off. He walked bouyantly through the winding little streets of the Village till he found Brenda's building, and then almost floated up the dingy stairs, singing a jaunty aria from Don Giovanni as he climbed.

He reached the top at last, dumped his suitcases on the

landing, and played a tattoo on the door with his fists.

I'm here, Brenda!

he bellowed. All packed?

Ready and waiting, he hoped.

The door opened. But it wasn't Brenda who answered. It was a man in a policeman's uniform, and his face was grim.

Hello, Mr. Glenn,

he said. I thought I'd find you

here. We've been searching all over for you.

Harry stepped back. What sort of joke is this? Where's

Brenda?

She's not here just now,

the officer said. Do

you have the cash on you?

What cash?

Harry countered.

The cash from the bank you robbed,

the policeman said,

pulling Harry inside and shutting the door. Harry saw that the

officer was somewhat taller even than his assumed six-three,

and fully armed.

I don't know what you're talking about,

Harry said.

Please don't make this difficult, Mr. Glenn. I know

perfectly well that you're the man who robbed the National

this morning, and I'm here to bring you in. Will you come

quietly, or do I have to take you?

Harry's stomach dropped about a foor. Wild schemes flashed through his head, of changing into a worm or an ameba and vanishing, but he rejected the idea. The jig was up. It was all over. He saw he should have maintained his code of ethics after all, and stayed away from any nefarious activities. He held out his hands, revealing the handcuff on one wrist. No use resisting.

Here,

he said. I give myself up. I confess. Take

me away.

The policeman stared at his hands with a strange smile on

his lips. You've already got one handcuff on. How come?

I'm too tired to explain,

Harry said wearily. He was

almost glad, now that the whole thing was over; he had never

deserved a girl as glorious as Brenda in the first place, and

he saw now that a lifetime of hiding behind a mask would have

been worse than a prison sentence.

Would this help you to make an explanation?

the

policeman said. He stretched out his own wrists. Harry stared.

On one wrist was the mate to the handcuff he was wearing. As Harry blinked in amazement, the form of the policeman wavered and melted, and in his place stood—

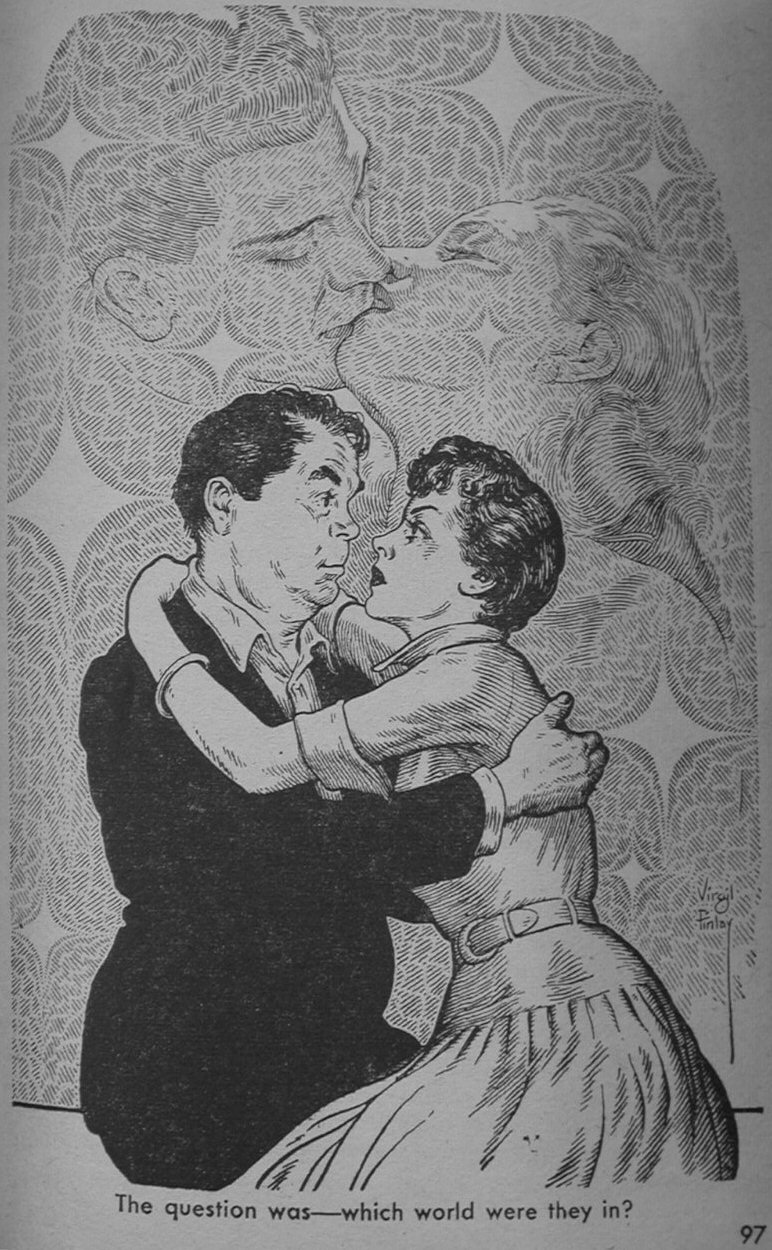

Brenda.

She was in his arms in a moment. He held her tight, dizzy with relief and bewilderment, and then pushed her away. Suddenly some of the answers entered his mind, and he gasped.

You, too!

He pointed at the handcuff. You have the

power too!

He flung himself down on the spidery black

butterfly chair, weak with amazement. She came over to him.

Yes, you silly,

she said affectionately. I was just

playing a game of cops and robbers with you. As soon as I saw the

account of the bank robbery, I put everything together and I knew

you had to have the power the same way I do! It was

the only explanation for the way those witnesses differed.

What a gigantic coincidence,

Harry said, barely managing

to croak in a whisper. That we should be at the same place at

the same time—

No coincidence at all,

said a piping voice from the floor.

I engineered it.

Harry looked down, not at all surprised

to see Quork, the miniature demon, there.

So you weren't a hallucination after all,

Harry said.

I'm a lot more real than you are,

Quork said pointedly.

Harry reddened, guessing his meaning.

You—you arranged the whole thing,

Harry said.

That's right,

said the demon, hopping up to the edge of

the chair. My employers felt it was too bad you two perfectly

good people had to be lonely and apart, too shy to ever approach

one another, and so we took this rather roundabout way of bringing

you together.

Harry looked at Brenda. She was still standing in the middle of the floor, looking as radiant as ever. She smiled at him.

Suppose you two hold out your hands,

Quork said. I'm

going to need those handcuffs for the next job.

Almost automatically, without thinking, Harry and Brenda held out their arms, and the handcuffs dropped off; Quork caught one neatly in each hand, lowered them, and sat on them.

Harry suddenly felt the change come over him, and he shut his eyes in terror. He knew he was back to his old body; the god-like personality projection must have vanished when the handcuff came off, and for the first time Brenda was seeing the real Harry Glenn.

Slowly, timidly, he opened his eyes. Brenda was still standing in the middle of the floor—but she, too had changed. She was a small, thin girl with curly, brown hair—a little pale, a little mousy-looking, but with an undeniable kind of unbeautiful loveliness about her.

Go on,

Quork urged. Get up and kiss her.

Harry got out of his chair and walked over to her. She was four or five inches shorter than he was, and she was looking up at him with a sort of wonder in her eyes.

No more masks,

Harry said slowly. They're all gone

now.

I know,

said Brenda. But we don't need them anymore,

do we?

I guess not,

said Harry. Our real selves will have

to serve the purpose.

He fumbled in his pocket. The money

was still there, a bulky package in its bank envelope. He

drew it out.

That's a lot of money,

he said.

Too much,

said Brenda. It'll spoil us.

Right,

Harry agreed. I'll mail it all back

tonight.

Brenda smiled—and her smile, Harry noticed, was a

warm and wonderful thing, with none of the flashiness of the

other Brenda. We can forget about New Mexico,

she said. I think we can be happy right here—the

real us.

I'm sure of it,

Harry said, as he pulled her toward

him. Let's start collaborating right now.

©1956, 1984 by Agberg, Ltd. Used by permission