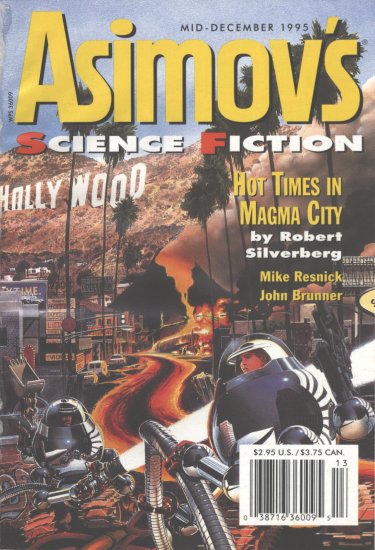

Hot Times in Magma City:

Lava in My Head

by Alvaro Zinos-Amaro

California time in Silverberg-land, once again. This novella,

published in 1995, is interesting for several reasons. It clearly

belongs to the near-future, L.A. based stories-which of course,

though having a common background, share little more. But this

story seems to me, more than others with the same setting, to be

fundamentally about people in the here and now, not as seen through one of

Silverberg's preferred sf-tools, such as telepathy for instance,

but seen as normal people, not extraordinary in any way. Au

contraire, most of the characters depicted in the novella are

less than exemplary specimens of the human species, to put it

mildly. They do not posses any gifts. They have not met alternate

version of themselves, or traveled through time, or been in

contact with aliens. They have only one factor in common: they

are in various stages of recovery, personal recovery that is,

from some kind of brought-on malady, whether it be boozing or

drug-taking or whatever else. The protagonist of the story, one

Cal Mattison, used to spend his life cruising from one bar to the

next, and generally getting involved in nasty physical

altercations the rest of the time. Very well, if the characters

do not give the story science-fictional credit, then what does?

California time in Silverberg-land, once again. This novella,

published in 1995, is interesting for several reasons. It clearly

belongs to the near-future, L.A. based stories-which of course,

though having a common background, share little more. But this

story seems to me, more than others with the same setting, to be

fundamentally about people in the here and now, not as seen through one of

Silverberg's preferred sf-tools, such as telepathy for instance,

but seen as normal people, not extraordinary in any way. Au

contraire, most of the characters depicted in the novella are

less than exemplary specimens of the human species, to put it

mildly. They do not posses any gifts. They have not met alternate

version of themselves, or traveled through time, or been in

contact with aliens. They have only one factor in common: they

are in various stages of recovery, personal recovery that is,

from some kind of brought-on malady, whether it be boozing or

drug-taking or whatever else. The protagonist of the story, one

Cal Mattison, used to spend his life cruising from one bar to the

next, and generally getting involved in nasty physical

altercations the rest of the time. Very well, if the characters

do not give the story science-fictional credit, then what does?

The lava-flows? Silverberg has extrapolated from known plate tectonics and created lava-flows and earthquakes in California in the near future. At least from a superficial point of view, this does not seem to be sf. There are quite a few natural-disaster stories that are described as science-fiction nowadays. Some of them, say David Brin's massive novel Earth (which I don't entirely like for other reasons) or Charles Sheffield's Aftermath, I think genuinely classify. When the natural disaster that sets things in motion is science-fictional, the rest follows. Consider Arthur C. Clarke's The Hammer of God. Summed up, an asteroid disaster story. But, of course, there is a lot more to it, because of the way in which Clarke focuses on the science-fictional details of his future, the technology as well as the emotions. It all depends largely on the approach taken, the style in which the natural disaster is dealt with: if it feels like a thriller or action story it's not likely to be sf. I wouldn't really describe Godzilla or Dante's Peak as science-fiction, no matter how bad my day (though Deep Impact and Amageddon, despite many quibbles, would probably make it).There are also various degrees of naturalness to a natural disaster. An asteroid impact is more probable than a black hole coming into contact with Earth, and lava eruptions more probable than an asteroid for that matter.

Which brings me to my first point, namely that though Silverberg's setting and characters do not posses any identifiable sf trademarks, his approach at the core is science-fictional, at least the texture of the story seems to feel that way. The lava and magma are described, in several nifty passages, as something science-fictional, some kind of deep, molten, inscrutable force, moving the characters in certain ways. They represent, in general terms of subtext perhaps, the fundamental alienness of the universe against which Silverberg has so often pitted his characters. So, though I don't think the novella fits into any traditional definition of sf, I can still understand it being treated as sf at a more profound level. It contains the classic Silverberg theme of redemption. The characters in the story are low-lives who are trying to move on, to make progress, to deal with their pasts and heal themselves, to whatever degree that is possible. Their work in the halfway-house is voluntary: as Mattison remarks at one point, they are not forced to do what they are doing. Some seem to be more deserving, or closer to, redemption than others. Mattison is working hard on this, on improving himself, making himself a better person. There are difficult moments, but he does his best. This subject is essential to all good fiction. Change, dynamics, growth, expansion. From here to the stars. What could possibly be more science-fictional? Reading this kind of story is obviously inspirational, for striving in others always reminds us to strive ourselves. When we read this novella we don't shrug Mattison and his crew off as a bunch of fucked-up losers, and turn, with smug superiority, to another story. Though their problems are largely self-inflicted, they are making an effort to change things. That is what is essential, this drive onward, making one's best effort every waking moment, every instant, no matter what has come before, or how hopeless the situation might seem. Classic stuff, good stuff. Silverberg's skillful writing turns this raw material into a finely honed novella.

It does not burn with intensity. But, in a way, this is good. Most of us to do not burn with intensity every day of our lives. Still, there are always challenges to be met, ways of improving our performance, both for ourselves and others. While it does not posses the brutality of The Second Trip, or smoothness of "Sailing to Byzantium", or the darkness of Dying Inside , it does seem to be one of Silverberg's more mature stories of the last few years, not so much in terms of conclusions, but more of premises. Throughout the novella, Silverberg sticks to Mattison's point-of-view: there are no authorial slip-ups (none that I could find), no little jumps out of character that tip-off the author's quiet, wise narrative voice, whispering some bit of information or other into our ears. This means that all events are filtered through Mattison's perceptions. He does not have, for obvious reasons, a very upbeat opinion of humanity. Yet however worthless we are, we are human beings, which somehow, somewhere means something. This dichotomy is nicely encapsulated in the novella:

Mattison doesn't like the idea of losing a member of his crew, even a shithead like Herzog. He knows that his crew is made up entirely of shitheads, himself included, and the fact that Herzog is a shithead does not invalidate him as a human being. Too much of the human race falls into the shithead category, Mattison realizes. If nobody in the world ever lifted a finger to save shitheads from their own shitheadedness, then almost everybody would be in trouble.

How very true.

I mentioned the lava as metaphor for alienness before. Within the story Mattison reflects upon lava as a metaphor for something else, for the anger he and people who have led themselves down destructive paths in general feel, which "keeps bubbling out all the time." This lava must be contained not only without, but within as well. Sometimes the most alien, incommunicable thing about a person can be what they refuse to acknowledge about themselves, and to confront. Mattison's outlook is about humanity is necessarily cynical (up to a point), like I mentioned before. Which means that, by association, the story's outlook is cynical. The writing reflects this and adapts to the characters, in several ways. Expletives, especially the word fuck, occur frequently, more frequently than anything by Silverberg which I've read since Hot Sky at Midnight . Also, there are certain ironic undercurrents to many descriptions. Consider the way Mattison thinks about his own history:

Mattison is a former casualty himself, who once carried a very serious boozing jones on his back that had a negative impact on his professional performance as a studio carpenter and extremely debilitating effects on his driving skills. His drinking also led him to be overly free with his fists...

The use of a mock-politically correct euphemisms like "negative impact" within the context produces a sarcastic overtone. Much of the writing in the novella is sardonic, sharp, sometimes even wry, in the classic underhanded Silverberg fashion. If the story is centrally concerned with the subject of redemption, it also manages to touch upon religion. During the trip from one emergency area to another, Matteson and the other voluntary workers witness a kind of sacrificial offering, being made by a newborn cult, presumably founded on the impressive outpourings of lava from underneath the Earth. I really enjoyed Silverberg's choice of words for introducing this scene: "Just how desperate some of these people are getting is something Mattison discovers when..." Not how carried-away, or extreme, but desperate. Clearly, this implies that resort to religious belief and more so religiously-induced action, as provoked by natural circumstances, is desperate. I couldn't agree more. Of course, Silverberg gives the Mexicans responsible for the sacrifice a collective voice through the character Annette Perez, who says, "If this was your neighborhood, carajo, and you had a god, wouldn't you want to ask him to stop this shit?" Which, though it does little to justify what is going on, certainly makes it more comprehensible to the reader from the point of view of a cultural/theological context. As is to be expected, the story offers no real resolutions. In the closing paragraphs, the lava outbreaks are getting worse, the situation is becoming considerably graver as a whole. The only way to go on is to keep struggling, to keep pushing on. We do not have solutions to most problems, but we do have the potential for many solutions. This novella, like some of Silverberg's best work, embodies this belief. Mattison sums it up: "What the hell. We do what we can, and hope for the best, one day at a time."

A few additional comments:

- I liked the lava protection suits. Very science-fictional. Reminded me, for some reason, of training suits used in the first part of Joe Haldeman's The Forever War, though any resemblance is surely superficial. I also enjoyed Silverberg's overt inclusion of a science fictional image, when describing them: "'How far are we from the nearest dedicated hydrant?' Mattison asks her, speaking like a space invader from within his lava suit..." Such references could easily bog down the story, but Silverberg wisely keeps them sparse, enhancing their effect.

- All the details of highway routes and suburb names added a nice realistic touch to the story, in my opinion (though some readers might find they are overdone, at least when considering the space allotted by a novella).

- For some reason Silverberg seemed a little fixated, whether consciously or subconsciously, on the comparison of fire and magma raging across territory to acne spreading across skin. Towards the beginning the story he offers us this image: "...but what everybody fears is that it in fact it's [the Zone] going to keep right on marching unstoppably westward until it gets to the ocean, like a bad case of acne that starts on a teenager's left cheek and continues all the way to the ankles." And then, considerably later on, "That great column of magma, rolling upward from the depths of the earth on a long slant to the west, began breaking through in a lot of other places, bursting out like an attack of fiery pimples across a wide, vaguely triangular strip..."